When you’re writing an essay on literature, you use more the skills of a reader. Of course, there has to be some analysis present, deep enough to answer the main question. But that’s the farthest it goes. With the classic English literature research paper, reading skills play a secondary role while your critical and analytical thinking is the main instrument to prove the thesis statement. However, that’s not all.

When you choose some literary work to focus on in a research paper, you study it inside and out – you know when it was created and in which circumstances; you explore who supports or opposes the ideas presented in the text; you participate in a discussion that can continue for years and do your best to contribute to it. And that’s the beauty of academic exploration, especially when you are really enthusiastic about getting to the heart of the matter. Here, in this article provided by our research paper help, you will find out how to write a classic English literature research paper properly and find all the information necessary for literature research paper writing. So, make yourself comfortable and enjoy!

How to Conduct a Research for a Literature Paper

The research is not all about typing your topic in the Google search bar and flicking through some articles that pop up in the first results. That looks more like choosing a new café to go with your friends to or looking for a gym with affordable prices. If you wish to produce a profound academic paper, you need to prepare a significant base which usually depends on the quality of the initial research. And in order not to make a blunder from the first steps, search for information in the right places which are:

- MLA International Bibliography. This is an online extensive database with about 3 million works on language and literature. It is regularly updated by the scientist and researchers from all over the world to keep it spot-on. It can be accessed through either your university or library websites.

- JSTOR. This search engine has a smaller database on literature, but offers more intricate search options – in the MLA bibliography you can search only the titles while the JSTOR gives a chance to search the text.

- John Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory & Criticism: This is actually a book that was published in 2004. But an online equivalent lets you search its content by keywords. Its peculiarities is that there are essays and works written by 275 literature scholars, and that’s already a solid reason to consult it.

- University Library: it is always a good idea to look through the resources of your college/university library. Firstly, there may be relevant academic papers written by the professors from your educational establishment, and if you use them in your research, you will certainly benefit from it. Secondly, there may be a dedicated department for your topic/field of studies.

These sources will help you to spot high quality and reliable information without the need to go through hundreds of meaningless articles and waste the precious time. And it’s always best to use them all together because this way you’ll get a broad overview of the scope you deal with in your research.

The next step after gathering all the links and books is to process the information. To get the most out of it, it is best to:

- Read through all the sources in search of relevant data.

- Mark arguments and statements that spark your interest or any other emotion.

- Note down everything that comes to your mind during reading – interesting passages, ideas, questions – literally everything, and don’t forget to indicate the places you quote or get your ideas from.

- Pay attention to conclusions as they contain the essence of every article or book.

- Define the terms that you don’t know or don’t understand as they can change your perception and the direction of thoughts.

- Perceive dead ends like challenges – it is quite common that you sift through the sources and find nothing (as it may seem to you). The truth is that you broaden your knowledge of the topic without noticing, and you should just keep researching.

Keep these little tips in mind while surfing through the data you’ve gathered.

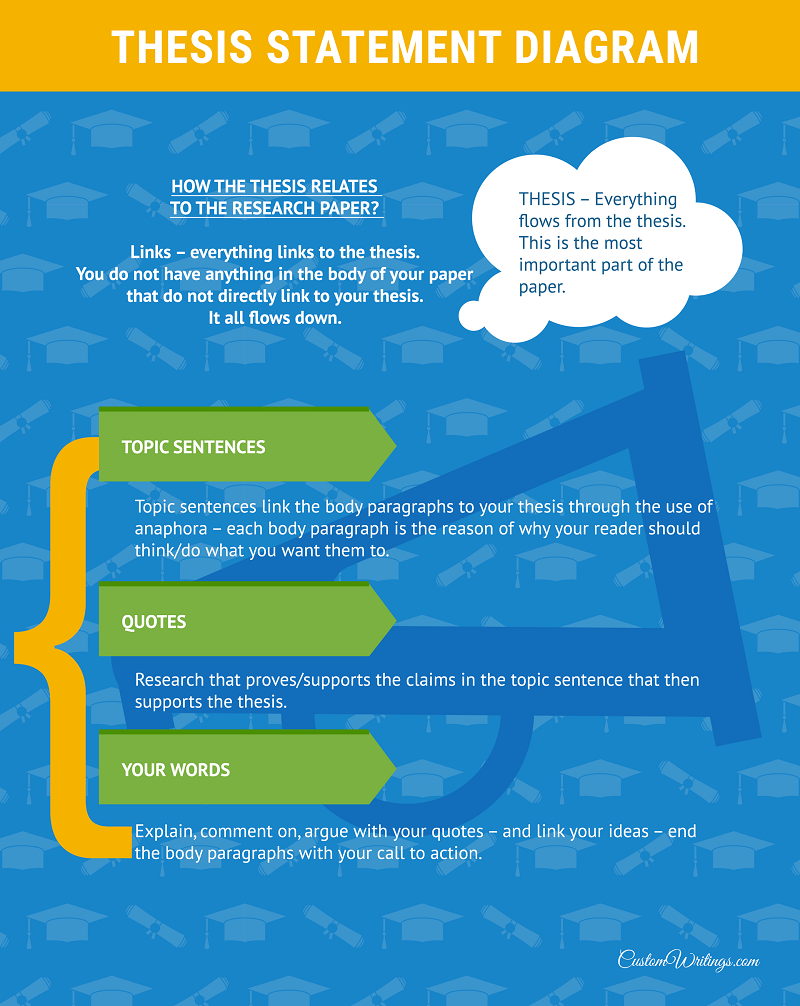

6 Tips on How to Develop a Working Thesis Statement for a Literature Research Paper

A thesis statement is a final destination of your literature research paper. It takes only one sentence, but defines the whole course of your exploration, so it’s necessary to understand the importance of its correct formulation. It is usually included in the end of the introduction and mentioned as a keynote though the whole paper. So, in order to create a provable and valuable thesis statement, you might want to:

- Avoid summarizing. You should state a specific goal you want to achieve within your research without retelling the plot of a literary work in focus.

- Answer the questions “What?” and “Why?”. What kind of claim are you stating and why should the readers care about it?

- Make it controversial. Simple and obvious statements don’t need any proving, so make sure your sentence sparks some stirring.

- Find proofs in the text. Your main argument should be supported and reflected in the text. Otherwise, your supervisor might consider it pulled out from the hat and pointless.

- Refrain from using vague language. If you want to research the negative consequences consequences of Hamlet’s actions, write it in plain words without any filler text.

- Add your further course of actions (optional). You may also include how you are going to prove the thesis statement and which aspects you will cover.

Despite the fact that this is only one sentence, you must allot a considerable amount of time to work it out. Every word in a thesis statement should be carefully chosen and considered, and the whole sentence should state a complete thought.

The last, but not the least – don’t use phrases like “In my view” or “I think” in your thesis statement because it will make your words less persuasive and create an impression that you don’t have enough evidence to prove your point. So, be attentive about how you lay out your opinions.

The Optimal Structure of an English Literature Research Paper

With research papers of any kind it is necessary to remember that everything goes from generalization at the beginning, then to more specific points reaching its climax in the middle, and in conclusion again to more general things. The usual structure of a literature research paper includes:

Abstract

This part can be one hell of a task because you must squeeze the essence of your whole piece in just 200 words mentioning the main questions, research methods, goals, and discussion. It is essential to remember that the abstract is the first thing everybody will read, thus it will be a point of decision for a reader whether to continue or not. The importance of this part is immense, so you might want to dedicate enough of your time to refine it to perfection.

Introduction

This is also a significant part of a research paper and it can be regarded as an extended version of an abstract. Here you will need to explain in detail why you’ve decided to take up this kind of research (personal interest, unexplored leads, incorrect perception, etc.) and where it will head throughout the whole piece.

Also, don’t forget to communicate a message that your research is really important to the chosen field of studies and provide decent reasons to prove it. The introduction that contains all this information will certainly create a positive impression.

Method

Do you use analysis or synthesis to research your topic? Have you conducted a survey? What other kinds of methods do you apply to explore the subject matter? All the answers to these questions and things concerning how your research is done should be included in this part.

Results

Here you need to lay out what you have discovered while proving your thesis statement. This can be figures, statistics, graphs, tables or just plain words that present your findings. It is not necessary to elaborate on them because you will need to do that in the discussion part.

Discussion

The discussion has to be connected with the thesis statement as well as the whole introduction because here you need to dwell upon not only the results of the research, but also on the aims you have achieved. This chapter must also include the importance of your findings and your own interpretations of the results.

Conclusion

The conclusion must discuss the connection between your findings and other researches as well as present the perspectives of the further studies. And besides restating your introduction, you can also suggest some improvements to your own research – that would be a good addition to a final chapter.

Bibliography

There is no paper out there that will be complete without the reference list. Gather all your sources, format your citations according to the chosen style and voila! The writing part is finished!

This is an overview of a typical literature research paper structure. But, of course, there can be different variations. So, don’t hesitate to consult with your advisor/supervisor on which elements exactly you need to include and which you can omit.

General Writing Guidelines to Improve Your Academic Style

We would like to top up our extensive manual on literature research writing with some general writing tips that will be useful both for literary papers and other academic entries. So, here we go:

- Include opinions that disagree with you together with critical interpretations – they will make your paper more interesting as well as stronger because this will show that you are confident enough in your theory and aren’t afraid of opposing views.

- Constantly check with your plan/outline because you can easily wander off to the unnecessary direction; unplanned writings can distract you from the main point and waste some of your precious time.

- Write your introduction while writing the main part of the paper – it will help you to keep it updated and release you from the necessity to rewrite it over and over again.

- Don’t focus too much on mistakes and punctuation. It is better to dedicate a separate session during which all you attention will be focused on tracking errors and inconsistencies.

- Separate editing sessions taking into account their purpose. If you want to check grammar, spend an hour or two looking purely for grammar errors. If you wish to review the punctuation, allot time specifically for this matter.

These classic English literature research paper writing tips, besides our detailed descriptions of the structure, research process and thesis statement, will make it possible to produce a complete and fully-featured research paper on literature. Just make sure that you spend enough time on each stage of writing – don’t postpone everything to the last month before the deadline because there won’t be any hours for planning and researching so essential to create a great academic piece.

So, choose the topic that interests you, follow our guidelines and make all the necessary preparations. This way everything will go smoothly.

Writing Hacks from Our Experts:

- Change the font of your research paper. After finishing the writing part you will get used to how your piece looks and may miss some mistakes just because your eyes will not notice them. But if you change the font, it will create an illusion as if you’re reading a paper written by someone else, and it will be easier to detect mistakes, especially the spelling ones.

- Always read the biography of the author who created the literary work you concentrate on and research the circumstances in which it was written. These details may help you understand the writer’s arguments better and your perception might change completely!

- Dedicate one paragraph to one point. Despite the obvious nature of this rule, most students forget about it and try to squeeze as much information in one paragraph as possible. So, be attentive here not to follow the steps of the majority.

Recommended reads