When you write a research proposal in history, it is important to make sure that your writing is always analytical and moves beyond just a simple description.

Professional historical writers tend to evaluate and interpret each source carefully, connect causes and effects, as well as weigh up events’ significance.

In general, the research proposal in history should be up to 2000 words in length. The main goal of the project is to demonstrate that you have research worth performing and manageable within the set period of time. In order to be worth performing, your research proposal in history must have a solid foundation and must make a significant contribution within the field of history.

Key Elements of a History Research Paper Proposal

A successful history research proposal essay should include the following elements. This list allows you to ensure that you fulfill your paper properly:

- Title, Abstract, Introduction. Your proposal should include a clear and concise title. It should accurately reflect the scope and focus of your research. An abstract is a brief summary of your proposal. An introduction provides an overview of the key points and objectives of your research, and thesis sample.

- Review of the Sources. In this section, you should provide a brief overview of the existing literature on your topic. You should also explain the significance of your research. Tell how it will contribute to the field of history.

- Research Questions or Hypotheses. Your research paper proposal questions or hypotheses should be clearly stated. They should demonstrate the originality and significance of your research.

- Methodology. This section should outline the methods and techniques you will use to conduct your research paper proposal. You should also explain how your methodology will help you answer your research questions or test your hypotheses.

- Timeline and Budget. Your research paper proposals should include a timeline. It will outline the key milestones in your research project. Add also a budget that details the resources you will need to complete your research.

- Conclusion. Your conclusion should summarize the key points of your research proposal on history. It should also make a compelling case for why your research requires funding attention.

Title Page

- Give personal information (your name, academic title, your position in your college, your birth date, contact details, nationality, etc.)

- The title of your future research report or history dissertation. Be careful when choosing the words for your title, and make sure they work well together. Provide a short, accurate, comprehensive, clear, and descriptive title that will indicate the subject of your research.

In order to come up with a concise title for your research proposal in history, the author has to be clear about the research focus. We recommend building up a title that includes no more than 60 characters. For example, your research proposal title might be ‘The Rise of Independent African Countries’, ‘Potential Change of Pope’s Political Power’, ‘The Influence of Hippie Culture on Today’s Culture’, ‘The Role of Women in Prehistoric Britain’, etc.

Clearly Define Your Research Topic and Objectives

Your research proposal topics and objectives should be clearly defined. They should demonstrate the originality and significance of your research. This will help to convince the reader that your research is worth pursuing. You should explain what you intend to research and why it is important. Tell what you hope to achieve by the end of your research project.

History PHD research proposal topics

Here are some history research proposal topics to inspire you:

- The influence of the Industrial Revolution on British society

- The role of women in the Civil Rights Movement

- The origins of the Cold War

- The impact of the Black Death on medieval Europe

- The cultural significance of the Harlem Renaissance

- The consequence of colonialism on indigenous societies

- The role of propaganda in World War II

- The impact of the internet on contemporary society

- The origins of the American Civil War

- The result of the French Revolution in European politics

- The impact of World War I on society and politics

- The role of religion in the American Revolution

- The effects of the Great Depression on American society

- The causes and consequences of the Vietnam War

- The influence of the Renaissance on European art and culture

These research proposal topics provide ample research opportunities. They offer valuable insights into historical events. Each research topic proposal will allow to observe the history issues thoroughly.

Start Writing a Research Proposal with a Clear and Concise Introduction

The introduction of your proposal should be clear and concise. It should introduce your topic, and explain why it is important. It should also provide an overview of your research questions or hypotheses. A catchy introduction can help to capture the reader’s attention and make them interested in your research topic.

Summary Statement/Abstract of the Research Proposal

This one-page summary provides a quick overview of the research topic. Besides, you have to focus on your proposal’s new, relevant and current aspects. While striving for clarity, you have to sum up the whole research – its question, the study’s rationale, its hypothesis, all the methods you have used (for instance, analysis procedures, design, instruments, etc.), and the key findings, as you would in complex data mining research projects. At the same time, you also have to mention some of the biggest challenges of your research.

Review of Research Literature

In your research proposal, you have to provide a precise and brief overview of the current state of historical research that is related to your research proposal. You should search for relevant literature. Analyze it to provide a solid foundation for your research.

- Talk about the most significant contributions that were made by the other historians. For instance, when the subject of your research is the well-known hippie culture, you may mention the works like ‘Influence of 1960s Hippie Counterculture in Contemporary Fashion’ by Abdullah Jaman Jony, Md. Asiqul Islam and Tanzila Tabassum or ‘The Hippies – An American “Moment’ by Stuart Hall.

- Discuss the theoretical part that you will use in order to support your research.

- Shows you are familiar with the ideas that you’re discussing and that you’re 100% conversant with their methodological implications.

- Specify the central problem that will later become the motive for your research. Be clear and concise about in what way your work and your findings will eventually contribute to the research base that already exists.

A thorough literature review can help you identify gaps in the existing research and demonstrate the need for your research project. It can also help you to refine your research questions or hypotheses.

Use Appropriate Sources

When conducting your literature review, be sure to use appropriate sources. Ensure that your sources are relevant. Also, you should make sure that they are reliable and up-to-date. Reliable sources are those that are trustworthy, and you can verify them. Some of them are peer-reviewed journal articles or books from reputable publishers.

Up-to-date sources are those that have authors published recently and reflect the most current knowledge in your research area. By using reliable and up-to-date sources, you can strengthen the credibility of your research proposal. It helps you to provide a more accurate and informative analysis of your topic. You should use primary and secondary sources to show a comprehensive analysis of your research topic.

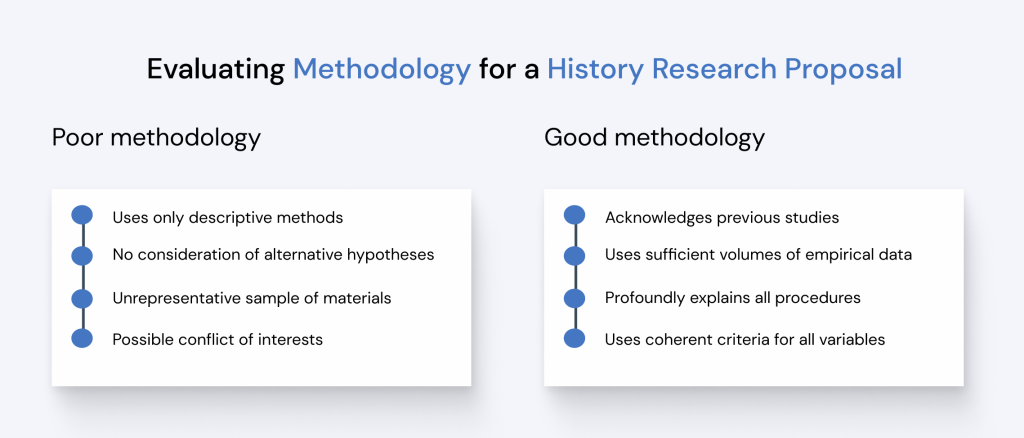

Methodology

The importance of the methodology section in a history research proposal can’t be underestimated because it lets your funding committee know how you’re going to deal with the problem of your research. It will become the kind of work route that will help you to describe all the activities that you’ll have to take in order to complete the project successfully.

- Selection of the location for your historical research.

- Participants of subjects of your research. Who is going to participate in your research? Notable or famous historians? Bloggers or professors from reputed institutions?

- Study instruments. Are you going to use questionnaires? Are they reliable? Why are you using this method exactly? For instance, for a topic like “Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination,” we’d recommend you to approach the experts of the Abraham Lincoln Association or Abraham Lincoln Institute (if possible) and ask them all important questions to make sure you’re able to support your research.

- Collect data. In what way are you going to carry out your research? What kind of activities do you plan to include? How much time do you need for this? If you’re going to watch documentaries, communicate with the representatives of the organizations that we’ve just mentioned, use library sources or anything else above that, and sort this out in your methodology section.

- Data review, analysis, and interpretation. At this point, you have a strong plan to process and code any sort of information, use some software (Zotero for free and easy citation management; Social Explorer to get access to current and historical census data; Mapping Social Movements that was created by Professor Jim Gregory at UW History Department and includes visualizations of loads of social movements that influenced the USA in the 20th century, and so on), sketch up some primitive tables for the historical data that you’re going to analyze in your research.

- Clarity. You should clearly explain your methodology. It should demonstrate that you have the skills and resources to complete your research successfully. This will help to convince the reader that your research is feasible. You should explain the methods and techniques you will use to conduct your research. Show how they will help you achieve your research objectives.

In your methodology section, you have an opportunity to also discuss all the ethical issues together with possible obstacles on your way to collecting data and other relevant material.

Describe Relevant Academic Resources

If you’re doing some historical research with institutional background, we recommend including the section titled ‘Description of the Relevant University Resources’. In this part, you have to let your committee know what your university has to offer on the chosen topic.

Mention the past contributions of the institution in the sphere of history and the research facilities, if any.

Results

Without a doubt, you do not have results when you’re at the stage of writing a research proposal. Nonetheless, you have to give some idea of what information you’re going to gather, what statistical data will be investigated, and what procedures will be used in order to answer the question of your research.

Provide a Realistic Timeline and Budget

Your timeline and budget should be realistic. They should demonstrate that you have carefully considered the resources you will need to complete your research. This will help convince the reader that you plan to complete the research. You should provide a detailed timeline outlining your research project’s key milestones. Show a budget detailing the resources you need to complete your research.

Include Appendices, If Required

In most types of academic projects, students are required to include appendices. Appendices usually contain all sorts of supporting documents that the author believes the committee will need in order to understand his proposal work. Besides, the author of the research proposal will often refer to his appendices, providing his readers with an opportunity to get back to them and read again.

Can one imagine a cup if he had never seen it before? Hardly. Consequently, students should also have detailed articles that show examples of worthy research topics, writing tips, and paper samples.

Use Clear and Concise Language

You should write your proposal should in clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using technical jargon or complex language that may confuse the reader. You should use suitable language and explain any technical terms that are necessary to understand your research.

Recommended reads

Pay Attention to Ethical Considerations

Acknowledge any potential ethical issues that may arise during your study. They can include obtaining informed consent from participants or protecting sensitive information. Address these concerns and discuss how you plan to navigate them ethically.

Editing & Proofreading

Once you are done with the conceptual work on your history research proposal, it is time to read it several times in order to edit and proofread it carefully.

Here are the points that we recommend you check when writing a research proposal on history:

- Check your titles, your abstract, and the general content of your research proposal to make sure they all correspond to each other.

- Make sure your project has a clear and logical structure. Your paper has to be intuitively simple, and your readers should get through your text without feeling lost at this or that point. All headings have to tell your readers where they are now and what should be expected next.

- Check your writing style to make certain it is declarative, reasonable, clear, and meets the existing requirements in the sphere of history.

- Add visuals and lists if necessary in order to demonstrate some abstract issues, dates, events, or people in a more understandable manner.

- Check if you highlighted important sections with white space.

- Ensure that your research proposal in history doesn’t include any spelling, style, or grammar errors. Typos should be corrected as well.

- You should also ensure that you format your proposal and that you include all the necessary sections.

If you have such an opportunity, we strongly recommend approaching some experienced academics and asking them to check and proofread your research proposal. This will help you to make sure that the paper conforms to the international and academic rules of your institution.

To make your research proposal top-notch, you should take care of the used language. You should try to avoid too primitive constructions, jargon, and long or hard-to-read sentences. Do not overuse high lexis to make the text readable. It is also necessary to stick to one writing style and tone.

Observe the Sample History Research Proposals

Also, to gain a better understanding of how to structure and format a history research proposal, you can observe sample thesis proposals. By examining these samples, you can familiarize yourself with the organization of such documents. Here are a few resources where you can find suitable sample thesis proposal and research proposal examples:

University Libraries: Many university libraries maintain online repositories. There, students can access any research proposal example. These resources are often available to students enrolled in history or related programs. You can check your university library’s website. You can also visit the library in person to inquire about the availability of such samples.

Academic Journals: Some academic journals publish a research sample proposal as part of their articles. These research proposals can serve as valuable examples for students. You can search for relevant journals in the field of history. You may explore their publications to find research proposals that align with their interests.

Online Databases: Online databases, such as JSTOR, ProQuest, or EBSCOhost, may contain any research paper proposal and history thesis samples. You can search these databases. Use keywords like “history research proposal” or “thesis proposal example” to locate relevant resources. Access to these databases may require a subscription through an educational institution or a library membership.

Academic Writing Websites: Numerous academic writing websites provide samples of research proposals and thesis proposals in various disciplines, including history. These websites often offer free access to sample documents, allowing students to study them as references for their own research proposals.

Our Website: You can also find any history research proposal sample at CustomWritings. We offer a wide range of free samples on any topic and subject. So, this may be another easy way for you to get a research proposal sample.

By examining various sample thesis proposals, research proposals samples, and sample thesis proposals, you can better understand the expectations and requirements for your own history research proposals. These samples can serve as valuable references. They provide guidance on effectively presenting research ideas, structuring the proposal, and supporting arguments with relevant evidence.

A Few Errors to Avoid

Even though a research proposal writing in history is completely your work, and you decide what data to include, the rule is the same for everyone – it has to be free from errors. Here are some of the most common mistakes that a research proposal author usually makes:

- Lack of evidence. No matter how many points or conclusions you make in your history writing, you have to support each with detailed and evidence-based examples. Do not just say something like ‘The document that I attached proves my point’. Instead, tell your supervisor in what way this piece of evidence is related to your argument.

The bad examples, in this case, might look like this: ‘The Mexican War dominated the short congressional career of Abraham Lincoln’. At the same time, the good one may sound like ‘According to the ‘Congress and the Mexican War’ by R.D. Monroe, Lincoln opposed the war that he believed was just a vote-getting trick, and he hoped that the fact that he doesn’t support the war would make his reputation in the US House of Representatives. - Vagueness. In the case of the research proposal in history, you have to stay away from all the truisms, empty unsupported statements, and broad generalizations. All these elements are usually seen in the opening parts of the research proposals, where the authors overuse general and grand claims. First, it makes your project uninteresting to your supervisor. Second, it prevents any sort of deeper reflection of whatever you’re trying to say in your research. It is crucial to remain specific, and concise, as well as support your claims with solid evidence. In case your research proposal contains a sentence that starts with ‘Since the beginning of our times’ or ‘Everyone knows that…’, you are making this mistake.

- Messy chronology. In the case of the research proposal in history, you will have to deal with many important dates. At the same time, your supervisor will be interested in now only how good you are at remembering them, but also how and what you think about them. This, however, does not mean that the chronological facts do not matter. You have to check every date to make sure that World War II doesn’t appear before the Battle of Waterloo.

Take your time to read your research proposal over and over again. This is not your research or dissertation yet. However, correcting all spelling, chronological, or grammar mistakes is a must. Approach your supervisor to see if he has any additional requirements for your work. Make sure that all the historical facts that you include flow in a logical order, while your introduction and conclusions do not contradict each other.

Finally, be careful not to judge historical events or people from the past. In other words, make sure to stay away from moralizing. Cheap statements are not going to take you into productive historical analysis that you actually should be doing.

If you learn how to write a History proposal, you will know that only dependable resources can help you manage the task. Below, you can find trustable sources to evidence your idea and get permission to write your academic paper in History.

So, history research proposal writing can be a challenging task. But by following the tips and guidelines outlined in this guide, you can write a winning proposal. It will help you secure funding and gain approval from your academic institution.

Remember to start with a clear and concise introduction. Clearly define your research topic and objectives. Conduct a thorough literature review. Explain your methodology. Provide a realistic timeline and budget. Use appropriate sources and clear and concise language. Proofread and edit your proposal. With these tips in mind, you can write a history research proposal that will help you achieve your research goals.

The creation of a History research proposal is a multistep assignment. One should include the most essential information to highlight the main idea of future research. Besides, you should select the correct methods and differentiate between dependable sources and fakes. If you find this assignment too hard, it will be better to ask for professional online help. Advanced writers explain the most difficult steps and assist their clients 24/7.