Many college freshmen don’t take essays seriously, associating them with assignments they used to write in high school. However, despite having the same name they are quite different. In high school, you could have gotten by summarizing a chapter from your textbook and throwing in a few original thoughts.

A college essay is as serious a research assignment as a dissertation – just on a smaller scale. You should demonstrate that you have understood the material, analyzed it and reached your own conclusions. In other words, don’t retell someone else’s knowledge but transform it.

In this psychology essay writing guide, we will tell how exactly it is done, step by step.

Pre-Writing Tips

Choice of Topic

If you are assigned with a topic by your professor you will not have to deal with this stage at all. Only in case you are assigned a topic but don’t like it, you should ask your professor if it can be changed or modified. If you provide good reasons the decision may be in your favor; If you are given some freedom, choose a topic that will show your knowledge and abilities in the most favorable light.

- Choose a topic you are interested in. Are you personally interested in a specific area of psychology? Have you recently read about a fascinating experiment? Do you know something that wasn’t part of the course and can impress your professor? When you are genuinely interested in what you write about, you are more likely to produce independent ideas and do deeper analysis;

- Narrow your topic down. “Depression” is not an essay topic, it is way too broad. “Primary Causes of Depression” is a bit better but still too general. Aim for something like “Factors Influencing the Increase in the Number of Depression Cases among American College Students in 2010s”;

- Write your topic down and check if it poses a question. The topic mentioned above, for example, can be boiled down to “Why students get depressed more often this decade?” An essay is supposed to be an answer to a question – if it isn’t, you simply retell knowledge without processing it;

- Discuss the topic with your professor to make sure your choice is valid.

As for more specific ideas, try these:

- Psychological concept, e.g. Flaws of Behavioral Theory of Leadership;

- Psychological disorder, e.g. Correlations between Eating Disorders and Suicide Risks;

- Type of therapy, e.g., Use of Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy in Depression Treatment;

- Area of human cognition, e.g. Causes and Consequences of False Memories;

- Analysis of a psychological experiment, e.g. Moral Implications of the Results of Milgram Obedience Experiment.

Reinterpret the Title/Question

The most important factor in your essay’s grade is whether you’ve managed to answer the question set in the topic. However, this shouldn’t be treated literally. If, for example, your topic is “Common Causes of Bullying in Middle School”, you shouldn’t just enumerate some factors that are commonly considered as such causes. You should evaluate the information available on the subject critically, review and discuss evidence and make your own conclusions. A good rule of a thumb is to rewrite any essay and title adding words “provide critical evaluation of the data” and “with reference to facts and examples”.

Find and Read the Sources

A number of studies suggest a significant correlation between the number of actively used sources and essay grades. When doing your research, make sure that you gather enough sources, but don’t add them purely to bloat your Works Cited page. If a source has no value to your work other than being an extra entry, drop it.

Proceed along these lines:

- If you are a given a list of literature on the topic, read it and make notes on info that may be useful;

- Start jotting down a rough plan of your essay. You already should define your main argument and single out a few crucial points in its support;

- Define the main authorities on the subject from the reading you’ve done so far;

- Check if any of them wrote a publication on the topic not mentioned in your list. You can always find up-to-date information on PubMed;

- Google your essay’s title and see if there are any reliable sources;

- Look in Pubmed using the keywords for your essay.

Planning

Psychology essays consist of the same parts as any other and follow the same rules. This means that you should let content words from the title/question lead you and organize the material you’ve gathered according to a traditional plan:

- Introduction;

- Body paragraphs;

- Conclusion.

Jot down the main points that are to be mentioned in each of body paragraphs and what evidence you will use to support your points.

Psychology Essay Writing Tips

Introduction

As a student of psychology, you should know about anchoring and adjustment effect: the first impression influences the final assessment. Most markers will form a definite evaluation of your essay after reading the first 1-2 sentences. It is much easier to make a good impression from the get-go than to adjust the first negative impression in positive direction.

In other words, if an essay starts off poorly, the marker will be biased against it. And vice versa – if it starts brilliantly, the marker will be more likely to forgive some flaws later on.

There is no single right way to write a good introduction, but some practices are universal. It should:

- Be short and focused, no more than about 10 percent of the overall essay size;

- Point out the main subject of the essay and the terms you are going to use;

- Describe the issues behind the basic question in the title;

- Chalk out your main argument and its structure.

Normally it is best to write the introduction last, when you have the rest of the essay ready.

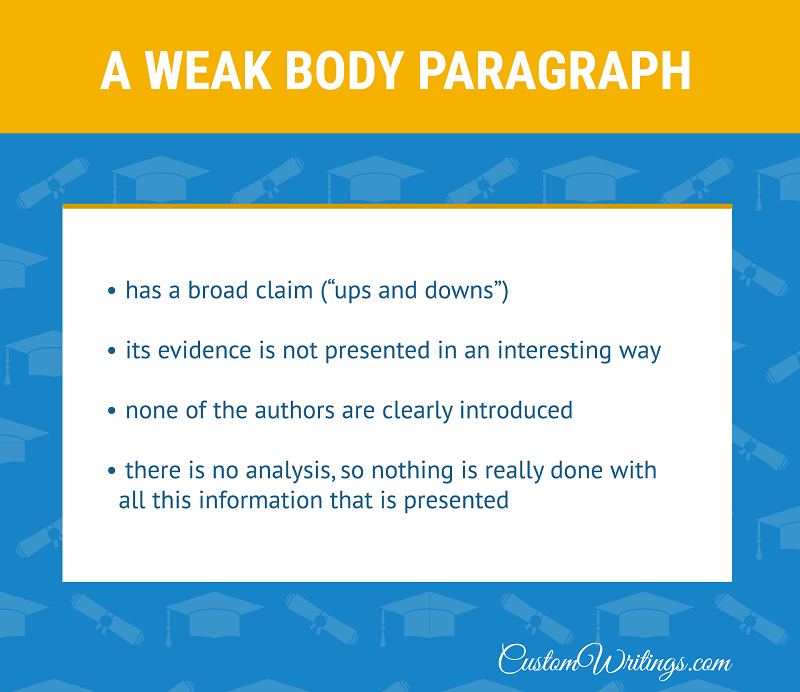

Body Paragraphs

The main part of the essay where you introduce all the new information, analyze it and try to find out the truth of the matter. This is the part you have most freedom with, but still you have to follow certain principles:

- Make a paragraph your primary unit of meaning. Every paragraph should deal with a single topic. If you notice that you’ve gradually moved on from one topic to another within a single paragraph, detach the additional point into a paragraph of its own;

- Don’t try to prove something. Your work doesn’t exist in isolation from the body of research done by other authors, and it is impossible to prove a theory in science. The best you can hope for is to find information that supports some previously made points – you cannot guarantee some new data doesn’t crop up to disprove your findings. It is especially true for psychology, because in this science the very concept of “proof” is very vague. Don’t write “This proves Jackson’s theory”. Write “This information is consistent with my theory”;

- Differentiate between sources of information. There are high-value, reliable sources (peer-reviewed journals) and low-value ones (newspapers, popular websites, bestselling books). The latter should be used sparingly, if at all;

- Avoid using emphatic language. Words like “terrible”, “ludicrous”, “unforgivable” have no place in scientific discourse. Let the objective weight of your evidence prove your point;

- Don’t rely on secondary sources too much and never cite them as primary ones. If you find a quotation from a publication in one of your sources and want to use information from it you should mention it “as cited in” your primary source. However, having too many such quotations looks unprofessional – if you use them extensively, get these sources yourself and read them. And never get tempted to cite them as primary sources – it is a very bad (and easily recognizable) practice.

Conclusion

When you’re done with body paragraphs, don’t just trail off. Introduction defines the first impression, but it is the conclusion that is fresh in the marker’s memory when he thinks what grade to give you.

- Don’t introduce new arguments. If they are necessary, find a place for them in the body.

- Summarize the key points and show how they answer they main question.

- If necessary, suggest ideas for future research. Don’t be vague: a sentence like “More research needs to be done before definitive conclusions are to be made” indicates that you have no idea what your study entails. Moreover – you haven’t even achieved any conclusion, i.e., didn’t finish your work. Indicate what this research is to be and why you think it is beyond the scope of your current task.

Post-Writing

Revision

Most students write their essays and believe that their job ends there. As a result, their grades often suffer due to mistakes and flaws that could have been corrected through only a superficial revision. Meanwhile, skilled writers spend just as much if not more time rereading, proofreading, correcting and revising their essays than they spent on writing per se. However, it is not the time you spend revising nor the number of revisions but rather how you approach the job.

- Let your essay cool off – let at least one night pass between finishing a draft and revising it;

- Revise according to a checklist (more on it a little later);

- Have somebody else read your essay and ask them for detailed criticism. Specify that you don’t mind getting a negative review. You may ask a friend or even hire a professional proofreading service;

- The more people you ask for opinions, the better.

Unfortunately, most psychology students understand revision as merely checking their writing for grammar and spelling mistakes. However, they mix it up with editing, which is just a part, and the least important one, of revision.

Revision checklist is a list of questions you have to ask yourself when revising the first draft of your essay. Ideally, you should reread your essay at least twice, each time concentrating on different aspects:

Structure and Content Revision

- Does the essay’s structure work as intended?

- Does the introduction serve as an effective hook for the reader?

- Do essay parts interconnect logically?

- Is each paragraph limited to a single point?

- Are the transitions between points smooth?

- Is the conclusion effective at summing things up?

- How relevant is your argumentation for the primary issue of the essay?

- Are the issues clearly expressed and analyzed?

- Does your argumentation have any obvious weak spots?

- Do you address them?

- Are there any issues left uncovered?

- Do you supply all your arguments with relevant evidence?

- Are you truly critical when reviewing the evidence?

- Do you look at things from your opponent’s point of view?

- Do you show signs of bias?

Style Revisions

- Don’t try to make your writing appear more scientific by using long words and psychological terminology and jargon. The ability to discuss complicated subjects in simple language is a skill you should try to develop early on;

- Don’t introduce more than one significant point per paragraph in the body of the essay;

- Use active voice whenever possible. Make exceptions only for the situations in which the actor is secondary to the action;

- Avoid long sentences, cut them into shorter ones when possible. As a variant, alternate sentence length: a longer one per 2 or 3 shorter ones;

- Eliminate clichés, repetitions and vague generalized expressions;

- Cut mercilessly. You may want to reread the essay one more time for this purpose alone: if a word, sentence or an entire paragraph is not necessary to understand the point, get rid of it. It is probably the single most important part of revising.

What Should Be Cut without Hesitation: Our Writers Know for Sure

If you cannot reach your word count with meaningful content, you should do additional research. Filler text not only does a poor job at masking the lack of meaningful content but also can turn into a bad habit that is very hard to break.

- Redundant nouns: e.g., “The interference facilitated the process of transformation”;

- Redundant verbs. Verbs “to do”, “to make”, “to have” and “to be” are often used with nouns that have their own verb forms (do research, have an inclination, make an upgrade);

- Weak modifiers. These words add nothing to the meaning of a sentence: usually, somewhat, pretty, quite, rather, normally, really, etc.

And finally – if you find that you don’t like how your essay turns out and still have free time, don’t hesitate to cut entire parts of it or start from scratch. Your purpose here is not to get rid of an assignment but to get the best possible grade – and the more you practice, the more likely you are to impress your tutors! If you are looking for an academic essay writing service, feel free to contact our company right now.